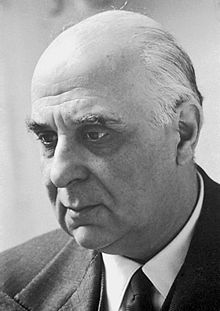

Yiannis Ritsos

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Yiannis Ritsos

| |

| |

Born

|

1 May 1909

Monemvasia, Greece |

Died

|

11 November 1990(aged 81)

Athens, Greece |

Occupation

| |

Nationality

| |

Notable award(s)

|

Lenin Peace Prize

1975 |

Yiannis Ritsos (Greek: Γιάννης Ρίτσος) (Monemvasia 1 May 1909 - Athens 11 November 1990) was a Greek poetand left-wing activist and an active member of the Greek Resistance during World War II.

Early life

Born to a well-to-do landowning family in the Monemvasia, Ritsos suffered great losses as a child. The early deaths of his mother and his eldest brother from tuberculosis, the commitment of his father who suffered with mental disease and the economic ruin of losing his family marked Ritsos and affected his poetry. Ritsos, himself, was confined in a sanitarium for tuberculosis from 1927 - 1931.

Literary start

In 1931, Ritsos joined the Communist Party of Greece (KKE). He maintained a working-class circle of friends and published Tractor in 1934, inspired of the futurism of Vladimir Mayakovsky. In 1935, he published Pyramids; these two works sought to achieve a fragile balance between faith in the future, founded on the Communist ideal, and personal despair.

The landmark poem Epitaphios, published in 1936, broke with the shape of Greek traditional popular poetry and expressed in clear and simple language a message of the unity of all people.[1]

Political upheaval and the poet

In August 1936, the right-wing dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas came to power and Epitaphios was burned publicly at the foot of the Acropolis in Athens. Ritsos responded by taking his work in a different direction: exploring the conquests of surrealism through access to the domain of dreams, surprising associations, explosion of images and symbols, lyricism which shows the anguish of the poet, soft and bitter souvenirs. During this period Ritsos publishedThe Song of my Sister (1937), Symphony of the Spring (1938).[1]

Axis occupation, Civil War and the Junta

During the Axis occupation of Greece (1941–1945) he became a member of the EAM (National Liberation Front), and authored several poems for the Greek Resistance. Ritsos also supported the left in the subsequent Civil War (1946-1949); in 1948 he was arrested and spent four years in prison camps. In the 1950s 'Epitaphios', set to music by Mikis Theodorakis, became the anthem of the Greek left.

In 1967 he was arrested by the Papadopoulos dictatorship and sent to a prison camp in Gyaros.

Legacy

The tomb of Yannis Ritsos atMonemvasia,Greece

Today, Ritsos is considered one of the five great Greek poets of the twentieth century, together with Konstantinos Kavafis, Kostas Kariotakis, Giorgos Seferis, and Odysseus Elytis. The French poet Louis Aragon once said that Ritsos was "the greatest poet of our age." He was unsuccessfully proposed nine times for the Nobel Prize for Literature. When he won the Lenin Peace Prize (also known as the Stalin Peace Prize prior to 1956) he declared "this prize is more important for me than the Nobel".

His poetry was banned at times in Greece due to his left wing beliefs.

Notable works by Ritsos include Tractor (1934), Pyramids (1935), Epitaph (1936), and Vigil (1941–1953).

One of his most important works is Moonlight Sonata:

I know that each one of us travels to love alone,

alone to faith and to death.

I know it. I’ve tried it. It doesn’t help.

Let me come with you.

—from Moonlight Sonata. Translation by Peter Green and Beverly Bardsley

Ritsos is also a Golden Wreath Laureate of the Struga Poetry Evenings for 1985.

Nikos Skalkottas

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Nikos Skalkottas

Nikos Skalkottas (Greek: Nίκος Σκαλκώτας) (21 March 1904 – 19 September 1949) was a Greek composer of 20th-century classical music. A member of the Second Viennese School, he drew his influences from both the classical repertoire and the Greek tradition.

Biography

Commemorative plate in Berlin

Skalkottas was born in Chalcis on the island of Euboea, to a poor family said to have been folk musicians and marble carvers.[weasel words] He started violin lessons with his father and uncle Kostas Skalkottas at the age of five, three years after his family moved to Athens because Kostas had lost the post of town bandmaster in 1906 due to political and legal intrigues (Thornley 2001). He continued studying violin with Tony Schulze at the Athens Conservatory, from which he graduated in 1920 with a diploma of high distinction.The following year a scholarship from the Averoff Foundation enabled him to study abroad.[citation needed] From 1921 to 1933 he lived in Berlin, where he first took violin lessons at the Prussian Academy of Arts with Willy Hess (Thornley 2001). Deciding in 1923 to give up his career as a violinist and become a composer, he studied composition with Robert Kahn, Paul Juon, Kurt Weill and Philipp Jarnach.[citation needed] Between 1927 and 1932 he was a member of Arnold Schoenberg's Masterclass in Composition at the Academy of Arts (Thornley 2001), where his fellow pupils included Marc Blitzstein, Roberto Gerhard and Norbert von Hannenheim.[citation needed] Skalkottas had been living for several years with the violinist Matla Temko (Thornley 2001); they had two children, though only the second, a daughter, survived infancy,[citation needed] and the end of their relationship increased his already-present feelings of self-doubt and insecurity (Thornley 2001). In 1930 Skalkottas devoted considerable effort to having some of his works performed in Athens, but they were met with incomprehension, and even in Berlin his few performances did not make much better headway. In 1931 he seems to have had a personal and artistic crisis: his relationship with Temko came to an end and he is also reported to have fallen out with Schoenberg, though the nature of their disagreement is unclear and Schoenberg continued to rate him highly as a composer.[citation needed] In any event Skalkottas seems to have composed nothing for at least two years.

In March 1933 he was forced by poverty and debt to return to Athens, intending to stay a few months and then return to Berlin. However, he suffered a nervous breakdown and his passport was confiscated by the Greek authorities (Thornley 2001) (apparently because he had never done military service)[citation needed]and in fact remained in Greece for the rest of his life. Among the various possessions he left behind were a large number of manuscripts; many of these were then lost or destroyed (although some were found in a secondhand bookshop in 1954).[citation needed] According to another account, his manuscripts were sold by his German landlady shortly after he left Berlin (Thornley 2001). In Athens Skalkottas sought other means of funding through scholarships or paid work as an orchestral player, but he was quickly disillusioned with the state of musical affairs in Athens at the time. Until his death he earned a living as a back-desk violinist in the Athens Conservatory, Radio and Opera orchestras. In the mid-1930s he worked at the Folk Music Archive in Athens, and did transcriptions of Greek folk songs into Western-music scores for the musicologist Melpo Merlier.

As a composer he worked alone, but wrote prolifically, mainly in his very personal post-Schoenbergian idiom that had little chance of being comprehended by the Greek musical establishment. He did secure some performances, especially of some of the Greek Dances and a few of his more tonal works, but the vast bulk of his music went unheard. During the German occupation of Greece he was placed in an internment camp for some months. In 1946 he married the pianist Maria Pangali; they had two sons. In 1949, at the age of 45 and shortly before the birth of his second son, he died of what appears to have been the rupture of a neglected common hernia, leaving some symphonic works with incomplete orchestration, and many completed works that were given posthumous premieres.

Music

See also: List of compositions by Nikos Skalkottas

Skalkottas' early works, most of which he wrote in Berlin, are lost, as are some of those written in Athens. The earliest of his works available to us today date from 1922–24; these are piano compositions as well as the orchestration of Cretan Feast by Dimitri Mitropoulos. Among the works written in Berlin are the sonata for solo violin, several works for piano, chamber music and some symphonic works. Although during the period 1931–34 Skalkottas did not compose anything, he resumed composing in Athens and continued until his death. His output comprised symphonic works (36 Greek Dances, the symphonic overtureThe Return of Ulysses, the fairy drama Mayday Spell, the Second Symphonic Suite, the ballet The Maiden and Death, works for wind orchestra and several concertos), chamber, vocal and instrumental works including the huge cycle of 32 Piano Pieces.

Besides his musical work, Skalkottas compiled an important theoretical work, consisting of several "musical articles", a Treatise on Orchestration, musical analyses, etc. Skalkottas soon shaped his personal features of musical writing so that any influence of his teachers was soon assimilated creatively in a manner of composition that is absolutely personal and recognizable.

Throughout his career Skalkottas remained faithful to the neo-classical ideals of Neue Sachlichkeit and 'absolute music' proclaimed in Europe in the 1925. Already in Berlin he was taking an interest in jazz and at the same time developing a very personal form of the twelve-note method, making use of not one but several tone-rows in a work and organizing these rows to define different thematic and harmonic areas. (For example, the Largo Sinfonico employs no less than 16 twelve-tone rows.) Like Schoenberg, he persistently cultivated classical forms (such as sonata, variations, suite), but his worklist is divided betweenatonal, twelve-tone and tonal works, all three categories spanning his entire composing career. Such apparent heterogeneity could have been intensified by a love of Greek folk music. The most striking example of his commitment to Greek folk music is the series of 36 Greek Dances composed for orchestra between 1931 and 1936, arranged for various different ensembles in the ensuing years and in part radically reorchestrated in 1948–49. About two-thirds of these dances are based on genuine Greek folk themes from different parts of the Greek mainland and islands, but the other third use material of Skalkottas's own composition in folk style.

Nevertheless, he remained sceptical of the attempts of his Greek contemporaries to integrate folk music into the modern symphonic style, and only juxtaposed and mixed folk, atonal and 12-note styles in a few works such as the incidental music to Christos Evelpides's 1943 fairy-tale drama Mayday Spell. Skalkottas was evidently reluctant to deploy the kind of structural and stylistic tensions that would have betrayed the integrationist ideals of his Schoenbergian inheritance. This could be seen (in terms of a comprehensive connecting impulse) as a link between the Second Viennese, Busoni, Stravinskyand Bartókian schools. Around 1945 he seems to have reappraised his aesthetic direction to some extent and written several works in a more conventionally tonal idiom - many of these have key signatures, for instance. Yet the general level of dissonance is not significantly lessened.

Posthumous reputation

It was only after his death that Skalkottas' music began to be played, published or critically estimated to a great extent, partly due to the efforts of friends and disciples such as John G. Papaioannou.

In 1988 a short documentary (60 mins) about his life and work was filmed with funding from the local authorities of Skalkottas' birthplace (the isle of Euboea) as well as the Greek Ministry of Culture.

In recent years,[when?] the Swedish record label BIS records has been recording and releasing his works on CD and SACD.

Giorgos Seferis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Giorgos Seferis

| |

Giorgos Seferis at age 21 (1921) | |

Born

| |

Died

|

September 20, 1971(aged 71)

Athens, Greece |

Occupation

|

Poet, Diplomat

|

Nationality

| |

Notable award(s)

| |

Giorgos or George Seferis (Γιώργος Σεφέρης) was the pen name of Geōrgios Seferiádēs (Γεώργιος Σεφεριάδης, March 13 [O.S. February 29] 1900 – September 20, 1971). He was one of the most important Greekpoets of the 20th century, and a Nobel laureate. He was also a career diplomat in the Greek Foreign Service, culminating in his appointment as Ambassador to the UK, a post which he held from 1957 to 1962.

Biography

Seferis was born in Urla (Greek: Βουρλά) near Smyrna in Asia Minor, . His father, Stelios Seferiadis, was a lawyer, and later a professor at the University of Athens, as well as a poet and translator in his own right. He was also a staunch Venizelist and a supporter of the demotic Greek language over the formal, official language (katharevousa). Both of these attitudes influenced his son. In 1914 the family moved to Athens, where Seferis completed his secondary school education. He continued his studies in Paris from 1918 to 1925, studying law at the Sorbonne. While he was there, in September 1922, Smyrna/Izmir was taken by the Turkish Army after a two year Greek military campaign on Anatolian soil. Many Greeks, including Seferis' family, fled from Asia Minor. Seferis would not visit Smyrna again until 1950; the sense of being an exile from his childhood home would inform much of Seferis' poetry, showing itself particularly in his interest in the story of Odysseus. Seferis was also greatly influenced byKavafis, T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound.

He returned to Athens in 1925 and was admitted to the Royal Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the following year. This was the beginning of a long and successful diplomatic career, during which he held posts in England (1931–1934) and Albania (1936–1938). He married Maria Zannou ('Maro') on April 10, 1941 on the eve of the German invasion of Greece. During the Second World War, Seferis accompanied the Free Greek Government in exile to Crete, Egypt, South Africa, and Italy, and returned to liberated Athens in 1944. He continued to serve in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and held diplomatic posts in Ankara, Turkey (1948–1950) and London (1951–1953). He was appointed minister to Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Iraq (1953–1956), and was Royal Greek Ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1961, the last post before his retirement in Athens. Seferis received many honours and prizes, among them honorary doctoral degrees from the universities of Cambridge (1960), Oxford (1964), Salonika (1964), and Princeton (1965).

Cyprus

Seferis first visited Cyprus in November 1953. He immediately fell in love with the island, partly because of its resemblance, in its landscape, the mixture of populations, and in its traditions, to his childhood summer home in Skala (Urla). His book of poems Imerologio Katastromatos III was inspired by the island, and mostly written there–bringing to an end a period of six or seven years in which Seferis had not produced any poetry. Its original title Cyprus, where it was ordained for me… (a quotation from Euripides’ Helen in which Teucer states that Apollo has decreed that Cyprus shall be his home) made clear the optimistic sense of homecoming Seferis felt on discovering the island. Seferis changed the title in the 1959 edition of his poems.

Politically, Cyprus was entangled in the dispute between the UK, Greece and Turkey over its international status. Over the next few years, Seferis made use of his position in the diplomatic service to strive towards a resolution of the Cyprus dispute, investing a great deal of personal effort and emotion. This was one of the few areas in his life in which he allowed the personal and the political to mix.

The Nobel Prize

George Seferis in 1963

In 1963, Seferis was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature "for his eminent lyrical writing, inspired by a deep feeling for the Hellenic world of culture." [1] Seferis was the first Greek to receive the prize (followed later byOdysseas Elytis,who became a Nobel laureate in 1979). His nationality, and the role he had played in the 20th century renaissance of Greek literature and culture, were probably a large contributing factor to the award decision. But in his acceptance speech, Seferis chose to emphasise his own humanist philosophy, concluding: "When on his way to Thebes Oedipus encountered the Sphinx, his answer to its riddle was: 'Man'. That simple word destroyed the monster. We have many monsters to destroy. Let us think of the answer of Oedipus." [2] While Seferis has sometimes been considered a nationalist poet, his 'Hellenism' had more to do with his identifying a unifying strand of humanism in the continuity of Greek culture and literature.

Statement of 1969

In 1967 the repressive nationalist, right-wing Regime of the Colonels took power in Greece after a coup d'état. After two years marked by widespread censorship, political detentions and torture, Seferis took a stand against the regime. On March 28, 1969, he made a statement on the BBC World Service [3], with copies simultaneously distributed to every newspaper in Athens. In authoritative and absolute terms, he stated "This anomaly must end".

Seferis did not live to see the end of the junta in 1974 as a direct result of Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus, which had itself been prompted by the junta’s attempt to overthrow Cyprus’ President, Archbishop Makarios.

At his funeral, huge crowds followed his coffin through the streets of Athens, singing Mikis Theodorakis’ setting of Seferis’ poem 'Denial' (then banned); he had become a popular hero for his resistance to the regime.

Other

In 1936, Seferis published a translation of T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land.

His house at Pangrati district of central Athens, just next to the Panathinaiko Stadium of Athens, still stands today at Agras st.

Blue plaque on Sloane Avenue, London

There are commemorative blue plaques on two of his London homes – 51 Upper Brook Street,[1] and in Sloane Avenue.

In 1999, there was a dispute over the naming of a street in İzmir Yorgos Seferis Sokagi due to continuing ill-feeling over the Greco-Turkish War in the early 1920s.

In 2004, the band Sigmatropic released "16 Haiku & Other Stories," an album dedicated to and lyrically derived from Seferis' work. Vocalists included recording artists Laetitia Sadier, Alejandro Escovedo, Cat Power, and Robert Wyatt. Seferis' famous stanza from Mythistorema was featured in the Opening Ceremony of the 2004 Athens Olympic Games:

I woke with this marble head in my hands;

It exhausts my elbows and I don't know where to put it down.

It was falling into the dream as I was coming out of the dream.

So our life became one and it will be very difficult for it to separate again.

It exhausts my elbows and I don't know where to put it down.

It was falling into the dream as I was coming out of the dream.

So our life became one and it will be very difficult for it to separate again.

He is buried at First Cemetery of Athens.

Works

Poetry

Prose

· Dokimes (Essays) 3 vols. (vols 1–2, 3rd ed. (ed. G.P. Savidis) 1974, vol 3 (ed. Dimitri Daskalopoulos) 1992)

· Antigrafes (Translations) (1965)

· Meres (Days–diaries) (7 vols., published post-mortem, 1975–1990)

· Exi nyxtes stin Akropoli (Six Nights on the Acropolis) (published post-mortem, 1974)

· Varnavas Kalostefanos. Ta sxediasmata (Varnavas Kalostefanos. The drafts.) (published post-mortem, 2007)

· Six Nights on the Acropolis, translated by Susan Matthias (2007).

English translations

· Complete Poems trans. Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard. (1995) London: Anvil Press Poetry. ISBN [English only]

· Collected Poems, tr. E. Keeley, P. Sherrard (1981) [Greek and English texts]

· A Poet's Journal: Days of 1945–1951 trans. Athan Anagnostopoulos. (1975) London: Harvard University Press. ISBN

· On the Greek Style: Selected Essays on Poetry and Hellenism trans. Rex Warner and Th.D. Frangopoulos. (1966) London: Bodley Head, reprinted (1982, 1992, 2000) Limni (Greece): Denise Harvey (Publisher), ISBN 960-7120-03-5

· Poems trans. Rex Warner. (1960) London: Bodley Head; Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Company.

Georgios Papanikolaou

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Georgios Papanikolaou

| |

Georgios Papanikolaou, as depicted on a commemorative Greek stamp in 1973

| |

Born

|

May 13, 1883

|

Died

|

February 19, 1962 (aged 78)

|

Residence

|

USA

|

Nationality

|

Greek

|

Fields

| |

Institutions

| |

Known for

| |

Georgios Nikolaou Papanikolaou (or George Papanicolaou; Greek: Γεώργιος Ν. Παπανικολάου; May 13, 1883 – February 19, 1962) was a Greek pioneer in cytopathology and early cancer detection, and inventor of the "Pap smear".

Life

Papanikolaou studied at the University of Athens, where he received his medical degree in 1904. Six years later he received his Ph.D. from the University of Munich, Germany, after he had also spent time at the universities ofJena and Freiburg.[1] In 1910, Papanikolaou returned to Athens and got married to Andromahi Mavrogeni and then departed for Monaco where he worked for the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco, participating in the Oceanographic Exploration Team of the Prince of Monaco (1911).[2]

In 1913 he emigrated to the U.S. in order to work in the department of Pathology of New York Hospital and the Department of Anatomy at the Weill Medical College of Cornell University.

He first reported that uterine cancer could be diagnosed by means of a vaginal smear in 1928, but the importance of his work was not recognized until the publication, together with Herbert Traut, of Diagnosis of Uterine Cancer by the Vaginal Smear in 1943. The book discusses the preparation of vaginal and cervical smears, physiologic cytologic changes during the menstrual cycle, the effects of various pathological conditions, and the changes seen in the presence of cancer of the cervix and of the endometrium of the uterus. He thus became known for his invention of the Papanicolaou test, commonly known as the Pap smear or Pap test, which is used worldwide for the detection and prevention of cervical cancer and other cytologic diseases of the female reproductive system.

In 1961 he moved to Miami, Florida, to develop the Papanicolaou Cancer Research Institute at the University of Miami, but died in 1962 prior to its opening.

Dr. Papanicolaou was the recipient of the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research in 1950.[3]

Papanikolaou's portrait appeared on the obverse of the Greek 10,000-drachma banknote of 1995-2001,[4] prior to its replacement by the Euro.

In 1978 his work was honored by the U.S. Postal Service with a 13-cent stamp for early cancer detection.

Discoveries

Pap test abnormal.

The fact that malignant cells could be seen under the microscope was first pointed out in a book on diseases of the lung, by Walter Hayle Walshe (1812–92), professor and physician to University College Hospital, London, in 1843. This fact was recounted by Papanikolaou.

In 1923 Papanikolaou told an incredulous audience of physicians about the noninvasive technique of gathering cellular debris from the lining of the vaginal tract and smearing it on a glass slide for microscopic examination as a way to identify cervical cancer. That year he had undertaken a study of vaginal fluid in women, in hopes of observing cellular changes over the course of a menstrual cycle. In female guinea pigs, Papanicolaou had already noticed cell transformation and wanted to corroborate the phenomenon in human females. It happened that one of Papanicolaou's human subjects was suffering from uterine cancer.

Upon examination of a slide made from a smear of the patient's vaginal fluid, Papanicolaou discovered that abnormal cancer cells could be plainly observed under a microscope. "The first observation of cancer cells in the smear of the uterine cervix," he later wrote, "gave me one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

Dr. Aurel Babeş, of Romania, made similar discoveries in the cytologic diagnosis of cervical cancer.[5] Babeş's 1927 work, however, was published in theProceedings of the Bucharest Gynecological Society, and it is unlikely that Papanicolaou was aware of it. Recent papers have proven beyond doubt that Babe's method was radically different from Papanicolaou's and that the paternity of Pap test belongs solely to Papanicolaou [Diamantis A, Magiorkinis E, Androutsos G. Different strokes: Pap-test and Babes method are not one and the same. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010 Nov;38(11):857-9.]

At a 1928 medical conference in Battle Creek, Michigan, Papanicolaou introduced his low-cost, easily performed screening test for early detection of cancerous and precancerous cells. However, this potential medical breakthrough was initially met with skepticism and resistance from the scientific community. Papanicolaou's next communication on the subject did not appear until 1941 when, with gynecologist Herbert Traut, he published a paper on the diagnostic value of vaginal smears in carcinoma of the uterus.[6] This was followed 2 years later by an illustrated monograph based on a study of over 3000 cases. In 1954 he published another memorable work, the "Atlas of Exfoliative Cytology", thus creating the foundation of the modern medical specialty ofCytopathology.

1 comment:

Blogs give the complete information about the topic on the internet. Blog is just like any another websites on the internet from which we get some things about the topic used on the blogs.logs give the full detail of information

Post a Comment